Falling in love with computers again at the Vintage Computer Festival East 2019

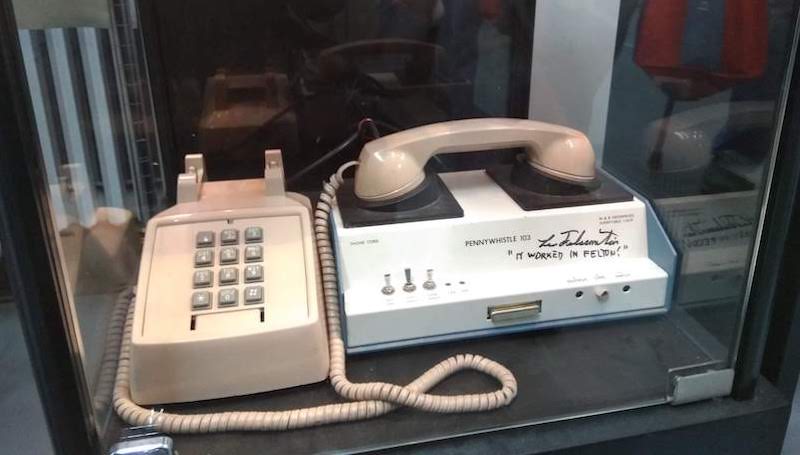

I attended the Vintage Computer Festival (VCF) East in New Jersey for the first time and it was such a compelling experience that I felt the need to write it up. So here goes! (photo above is of an early modem)

I attended the Vintage Computer Festival (VCF) East in New Jersey for the first time and it was such a compelling experience that I felt the need to write it up. So here goes! (photo above is of an early modem)

This was such a wonderful experience! I went with Tiffany Tseng, a New Jersey local. We were initially worried about what the crowd was like. It is not usual to be the only young women of color in a tech event, especially one focused on an earlier decade. It’s with great relief that I say everyone we talked to was nice, friendly and was very excited to share their knowledge about vintage computers! Most of the exhibitors I met were engineers or hobbyists who had fond memories of using these machines in their younger years and spent a lot of time to get them working in a modern day setting.

My first stop was the vintage plotter stationed by the ever lovely Paul Rickards, who was the reason that I had heard about the event. I felt like a kid in a candy shop watching all the different plotters in action. The highlight was a Roland DXY 990 flatbed-style plotter from the 80s. Ensuring that paper doesn’t shift during drawing is a problem that most of us Axidraw plotter users face. The Roland DXY 990 solved this by holding paper in place with static electricity. We could feel it ever so slightly on the backs of our hands. It’s 2019 and I am struggling with ways to hold my paper down only to discover that this was a problem that was so elegantly solved a good 30 years ago!

Left: an Apple plotter making a dual-colored print. Note how it would travel all the way to the left to a little toggle to rotate the pen holder to change colors! I was tickled by how the engineers decided that it wasn’t worth building a little motor into the pen holder and that it was just easier to do that instead. Also note how the circles are basically drawn as a series of short, straight lines. Right: a Roland DXY 990 flatbed with static electricity paper hold.

A plotter that looks like a cassette recorder!

— recursive (@recursive) May 6, 2019

An astute observation about a mini plotter at VCF!

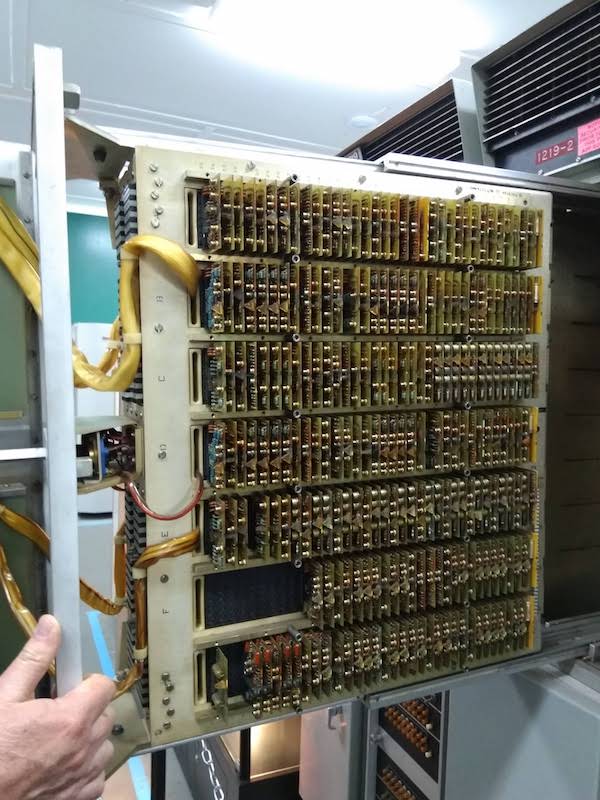

The venue of VCF itself had a vintage computer museum. We were lucky, just as we walked in, a VCF volunteer William Dromgoole was working on a UNIVAC 1219 mainframe computer that used to live on a Navy ship. This particular model of the UNIVAC was designed for military use and had been used for calculating missile trajectory. The doors and covers had secure latches and handles designed to withstand the presumably rocky journeys on the sea. We got to see it in action running a diagnostic program which was read out of Mylar punch tape, a time consuming process only rivalled by the follow-up step of rolling it back up with a hand-cranked tape roller.

The UNIVAC 1219 computer and its internal logic modules.

The UNIVAC 1219 computer and its internal logic modules.

Getting a tour of the UNIVAC was an extremely emotional experience for me. The engineer explained to us what it took to debug a failing diagnostic test, flipping through heavy stacks of manuals describing each error code and how it could map to a particular logic module card. Each of these circuits would represent a single logic gate (NAND, inverter, etc), from which individual instructions were composed of. It blew my mind to be able to see the itty-bitty parts that a computer is made out of. Here they were, the little logic gates made up of transistors that I was forced to learn about in computer science classes – I knew they were real and the building blocks of computer logic, but I had never seen them in such a way. It was such a powerful realization that computers were machines built using physical, analog parts. Our magic digital devices are really powered by bits of plastic, silicone and wires – it was beautiful.

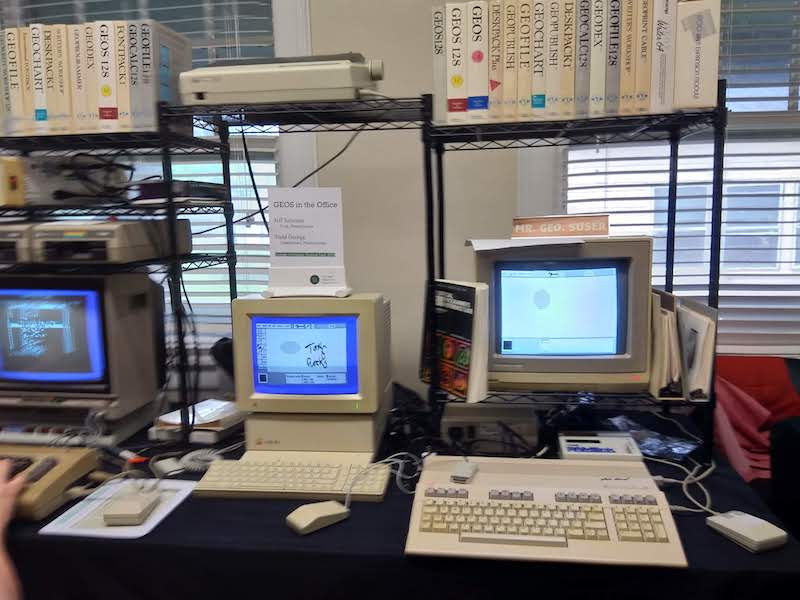

GeOS running on Commodore 128 and Apple IIGS machines.

GeOS running on Commodore 128 and Apple IIGS machines.

A Commodore keyboard with special characters from the PETSCII character set.

I truly enjoyed the tactile experience of vintage computers. Almost all the computers and devices at the exhibit was working and we could interact with them. I lost count of the number of different keyboards we marvelled at, each with different layouts and character sets. You could tell that these machines were lovingly restored and cared for. Every now and again, you’d hear a visitor compliment an exhibitor on the condition of their machine, “you’ve had this for 20 years? it looks almost brand new!”

A Commodore keyboard with special characters from the PETSCII character set.

I truly enjoyed the tactile experience of vintage computers. Almost all the computers and devices at the exhibit was working and we could interact with them. I lost count of the number of different keyboards we marvelled at, each with different layouts and character sets. You could tell that these machines were lovingly restored and cared for. Every now and again, you’d hear a visitor compliment an exhibitor on the condition of their machine, “you’ve had this for 20 years? it looks almost brand new!”

The interactive nature of the exhibit also made me realize quite quickly that I have been conditioned to use modern day GUI and that knowledge does not always transfer over. Some elements have persisted over the decades, such as the recycle bin, which we saw on an instance of GEOS, an operating system fron the late 80s. It was also ‘windowed’ in the sense that there was a single window for traversing directories. However, unlike a ‘Back’ button that we’re used to, you had to click on a corner of the window that resembled flipping back through the pages of a notepad. It’s a little hard to describe with words, so here’s a screenshot from GeOS Wikipedia page:

I was also fascinated by the modularity of systems. When I think of computers, I think of laptops now. I think of computers as single, whole units with irreplaceable parts. But for the most part of history, that wasn’t the case. We saw industrial computers with slots that could be customized with circuit boards. Input and output devices could be swapped out. My favorite example for modularity was a SCELBI microcomputer, which used a cassette tape for data storage. But instead of finangling with cassette tapes, the exhibitor, Mike Willegal substituted an iPod for the cassette tape! As long as the device can output to a 3.5mm audio jack, it works! This gave me a great satisfaction for the persistence of interface standards. Side note, the concept of the size of a microcomputer was a little different back in the late 70s than it is now: The SCELBI was a about the size of a large breadbox.

Mike Willegal and his SCELBI running a game of hangman. An oscilloscope was used as the display unit. Note the iPod replacement for the cassette tape data storage. Note the different line-in-square characters that could be used to draw graphics.

Mike Willegal and his SCELBI running a game of hangman. An oscilloscope was used as the display unit. Note the iPod replacement for the cassette tape data storage. Note the different line-in-square characters that could be used to draw graphics.

Another example of a hack (or co-opting) of technology was the use of MIDI connectors. MIDI stands for Musical Instrument Digital Interface and was initially used to connect with instruments that made sound, but an engineer somewhere got creative and used it to create a networked multi-player first shooter game, MIDI maze for Atari ST machines. For something that was built on co-opted technology, the game worked super smoothly and had negligible latency.

Atari ST computers running MIDI Maze at Peter Fletcher’s exhibit.

Atari ST computers running MIDI Maze at Peter Fletcher’s exhibit.

One of the loudest, but also most fascinating was a working Teletype Model 33 ASR exhibited by Hugh Pyle. If you’ve never used a Teletype machine before, just imagine using a CLI, but on a typewriter that prints your typing as well as the CLI response to paper. It wasn’t too different from using a terminal on a modern computer, but you couldn’t hit backspace or undo. I was initially curious about why they were used as terminals, when this was also around the time that punchcards and CRT display terminals were introduced. Turns out that CRT displays were really expensive at the time. In contrast, teletypes were readily available due to their historical use in newsrooms to transmit text. They turned out to also be great as computer terminals. The model we saw also could read/write punch tape as a way to store data or your programs.

A Teletype in action, printing an ASCII apple emoji

My favorite thing was finally getting first-hand experience with punchtape. Physical tape as memory, read by the machine to produce corresponding ASCII commands on a mechanical keyboard pic.twitter.com/PcaQvMThOP

— Tiffany Tseng 🍡 (@scientiffic) May 7, 2019

Tiffany’s tweet about the Teletype and her experience with physical tape.

Imperfections of the physical machines that add to the charm of it. Tiffany remarked on the quality of indicator lights on the UNIVAC. I later learned that these computers were likely made prior to the widespread usage of LEDs, and the glow from the neon bulbs. LEDs would yield brighter and more even lights, but one could argue that the beauty of these vintage machines lie in the nature of the physical parts that they were built with.

It was also striking to note that all of this history is being preserved by people who lived in that era of what we now know as “vintage”. I asked each exhibitor why they got into vintage computing and received different, but truly wonderful responses. They all had stories to share about their first time with the computer, teletype, whether they were introduced to it as a child, or worked with it as an engineer before they retired.

What happens when that generation ends though? Pyle had to send the Teletype which rescued from Craigslist to an engineer several states away who used to service them for a living. Who will repair Teletypes when these engineers are gone? Will they be forever lost? No doubt that videos and documentation will persist, but if nothing, this festival had shown me that the physical experience of interacting with a computer is irreplaceable.

My computing setup in 2019. A Macbook, a DELL LCD monitor, a Leopold mechanical keyboard and too many houseplants.

My computing setup in 2019. A Macbook, a DELL LCD monitor, a Leopold mechanical keyboard and too many houseplants.

I also started wondering what will we see at the Vintage Computer Festival 50 years from now? I am already imagining tables of Nintendo devices and pre-USB C Macbooks finding their places in those exhibits. Which software will we showcase? The web is remarkably great at backward compatibility, will that always be the case? I am always wary of standards or ‘best practices’ that are not built on browser APIs. Will we see virtual machines and Docker containers running copies of our favorite operating systems and games? Will the experience of using it be the same without the accompanying hardware? Also, perhaps the crowd would be more diverse? It’s hard to deny that computing was once a privilege only made available or marketed to a specific demographic. But that’s a topic for another conversation.

Either way, I’m looking forward to VCF East 2069. What do you think will be on exhibit then?