History of Computer Art -- Part 1: Computer Graphics

I’m writing a series of blog posts on computer art history from the 1960s onwards. This is the first part and we’ll talk about the early beginnings of computer graphics. This is part of my work during a week-long programming retreat at the Recurse Center.

The birth of computer graphics

Compilation of covers from Computer Graphics and Art publication from 1976-19771

Compilation of covers from Computer Graphics and Art publication from 1976-19771

Computer graphics had its roots in practical applications. The existing forms of print like typewriters and printers were inadequate to represent visual data. Imagine if you had a series of data from a sensor. Without a way to graph it, you would have to scan through pages of data to detect any sort of pattern.

To fulfil this need, drawing instruments like the plotter or cathode ray tube (CRT) display were developed for that specific purpose of visualizing data. They were not designed with aesthetic output in mind – a lot of graphics from the era consisted mostly of lines, which allowed for geometric shapes and grids. This was partly due to the limitation of technology, but also for the lack of need, but artists figured out ways to simulate them anyways. For example, textures or color gradients were not built in features of CRT displays or plotters, but still artists found ways to layer lines or characters to create interesting textures.

These devices were mostly designed and used for drawing graphs and diagrams. This limitation informed a lot of the styles of art that were created using these devices, which when viewed today is interpreted as “retro” or “minimalist”.

I couldn’t decide on which pieces to show you, so here’s a flip through of Computer Graphics and Computer Art by H.W. Franke, published in 1971 to give you an idea of the aesthetic.

Computers back then

To talk about the history of computer art, we must first talk about the history of computers. This wouldn’t be a deep dive, but just enough for you to get a picture of what it meant to use a computer, and who you had to be to get access to one.

IBM 7094 mainframe with all its parts 2

IBM 7094 mainframe with all its parts 2

To set a scene, the early 1960s was the era when computers were expensive and mostly found in research or academic facilities with their own computer labs. The de facto mainframe, the IBM 7090 Data Processing System would set you back a cool USD 2.9 million back in the day 3. That’s an equivalent of USD 25 milion in 2019, which gives you an idea of its affordability. It’s also interesting to note that the IBM 7090 in particular was built with engineers and scientists in mind.

Operating a mainframe computer lab required a set of technical staff to run the machines. The computer wasn’t a single unit like we know it today. The mainframe had to be used in conjunction with a series of peripherals: magnetic tapes for storage, punchers to write instructions, printers for output, card readers to convert punch cards to magnetic tape so it can be more quickly read by the computer, and so on. At the very minimum, the IBM 7090 consisted of eight different units 4. Sometimes I think about this when I complain about how heavy my 3lb (1.4kg) laptop is. Needless to say, running the mainframe wasn’t a casual affair.

In fact, most programmers barely saw the mainframe. More often than not, they would type out their code on a card puncher, hand it to a person behind the door at the computer lab, wait for a bit and get handed back the results of their code. Programmers were not afforded the luxury of instant feedback like we are today. I also think of this whenever I get impatient waiting for my unit tests to pass.

IBM 029 card puncher in action 5

Access to computers

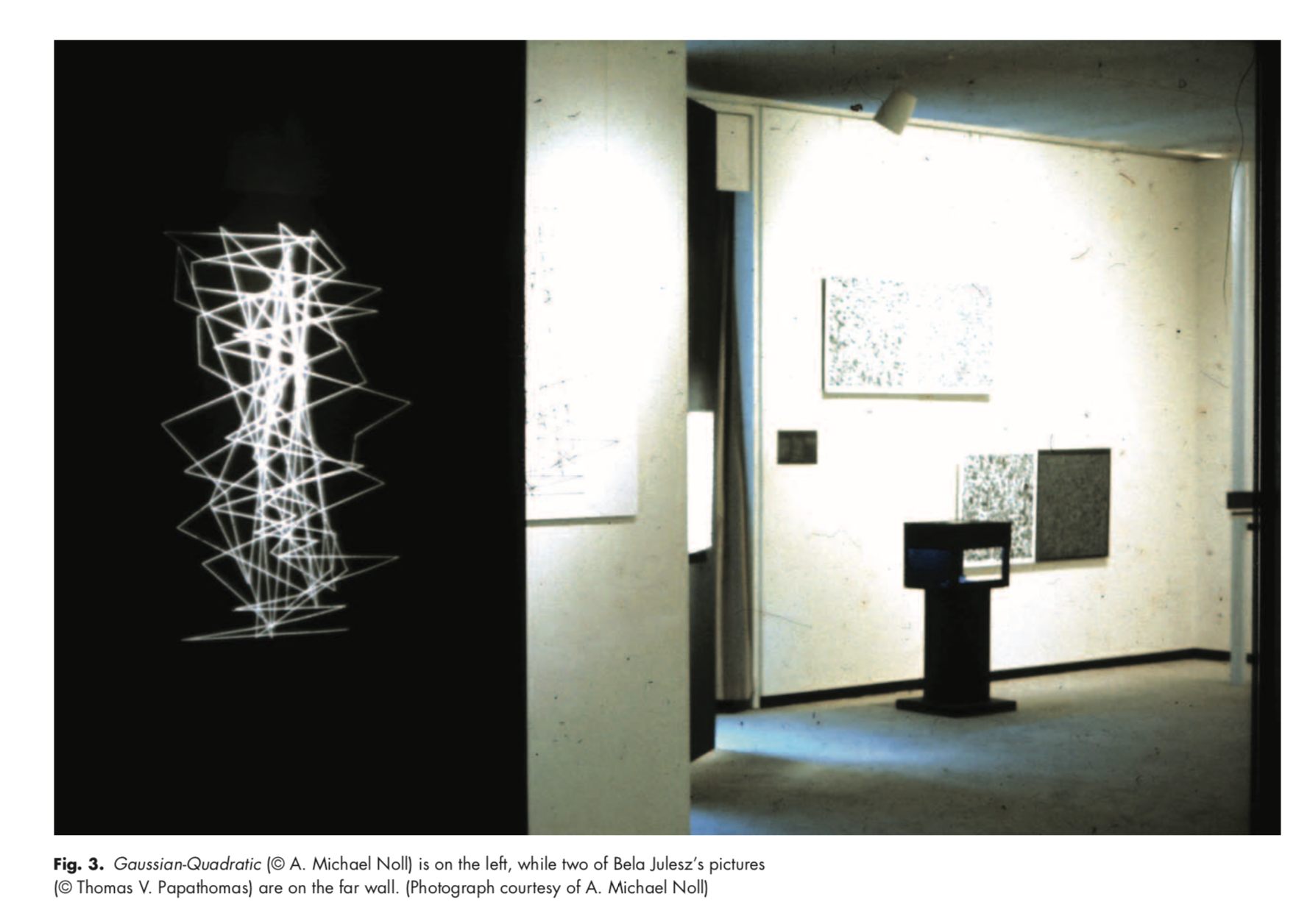

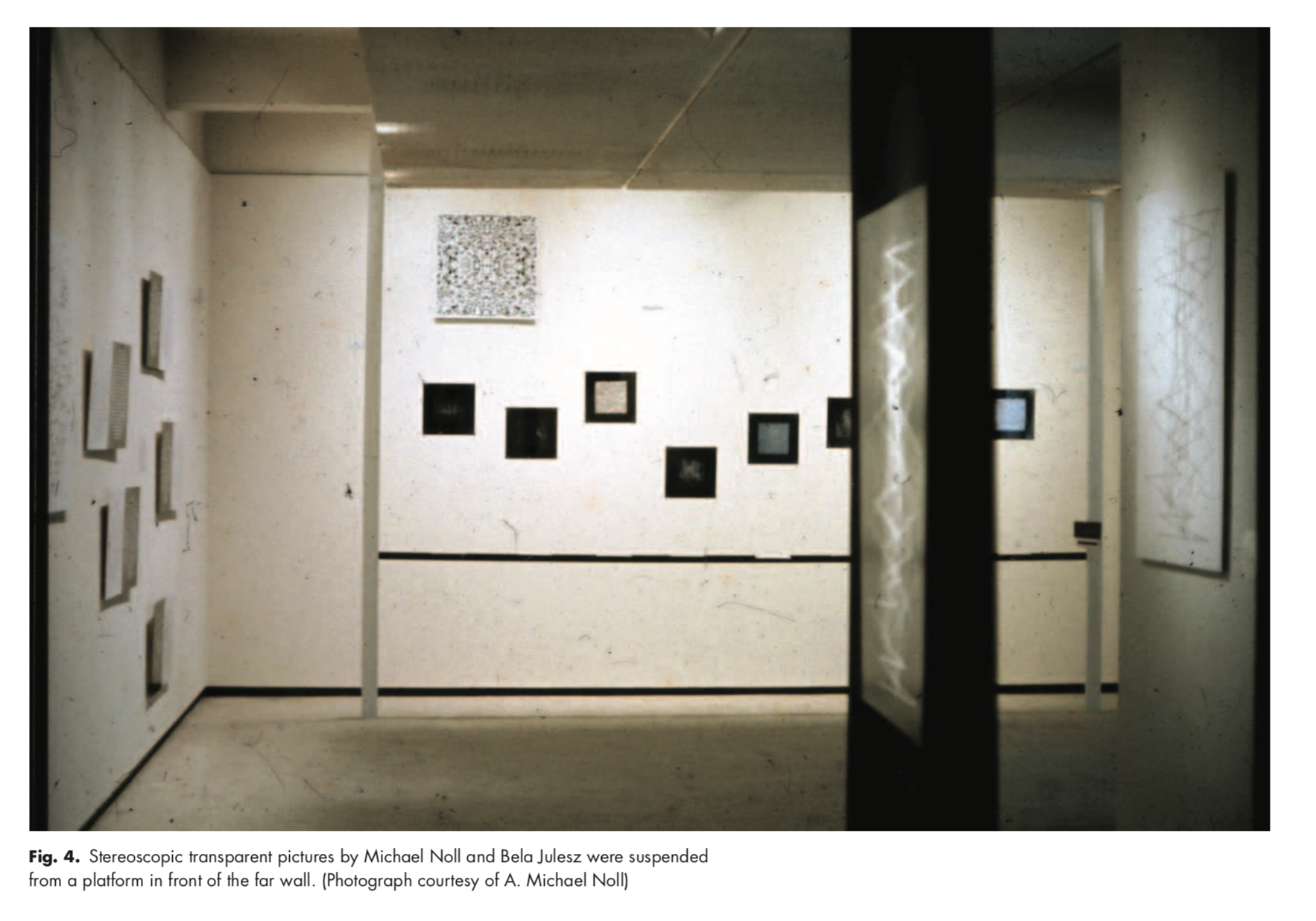

Consequently, the first few people who created computer art were not artists, but mathematicians, scientists and programmers who had access to these computers. One of the first computer exhibitions in North America was at the Howard Wise Gallery in New York City in 1965, showcasing works by two Bell Labs researcers, Michael A. Noll and Bela Julesz. Noll and Julesz worked on the IBM 7094 and a SC-4020 microfilm plotter. AT&T, who owned Bell Labs, initially did not want the exhibition to take place because they were worried that local regulators would “see the creation of art at Bell Labs as a superfluous waste of telephone charges by the monopoly” 6. The show itself was not well received by reporting art critiques, one even scathingly reviewed, “so far the means are of greater interest than the end, this revolutionary collaboration resulting in bleak, very complex geometrical patterns excluding the smallest ingredient of manual sensibility” 7 (emphasis mine).

Computer-Generated Pictures exhibit at the Howard Wise Gallery 8

Computer-Generated Pictures exhibit at the Howard Wise Gallery 8

This tickles me so much because in 2019, computer art has gained so much more attention as a medium of art. In fact, just in the past year, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the MoMA in NYC and the Whitney (which is still ongoing until Aprl 14, 2019) have all had dedicated exhibitions to a retrospective of computer art, all of which seemed to be very much enjoyed by the general public.

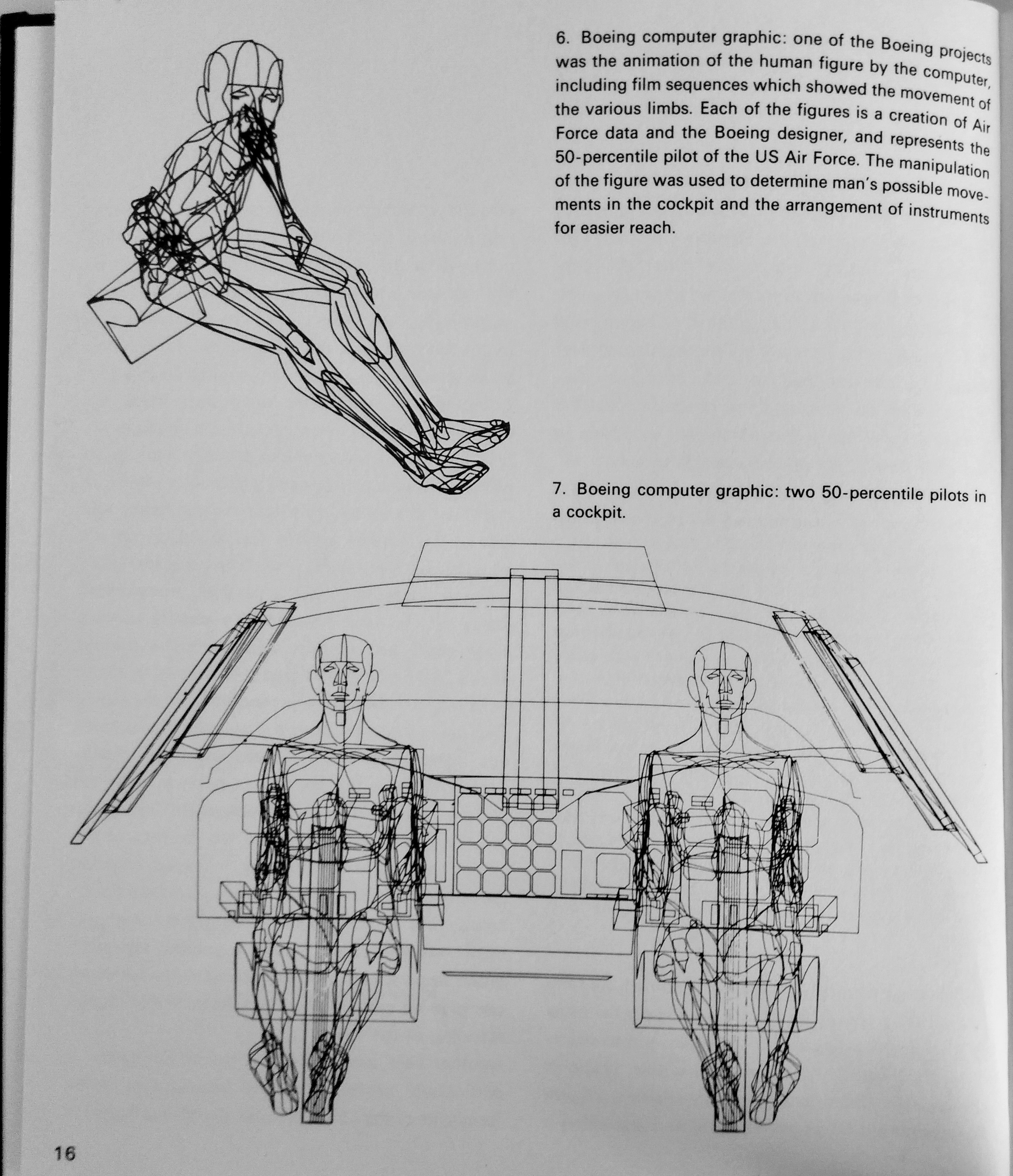

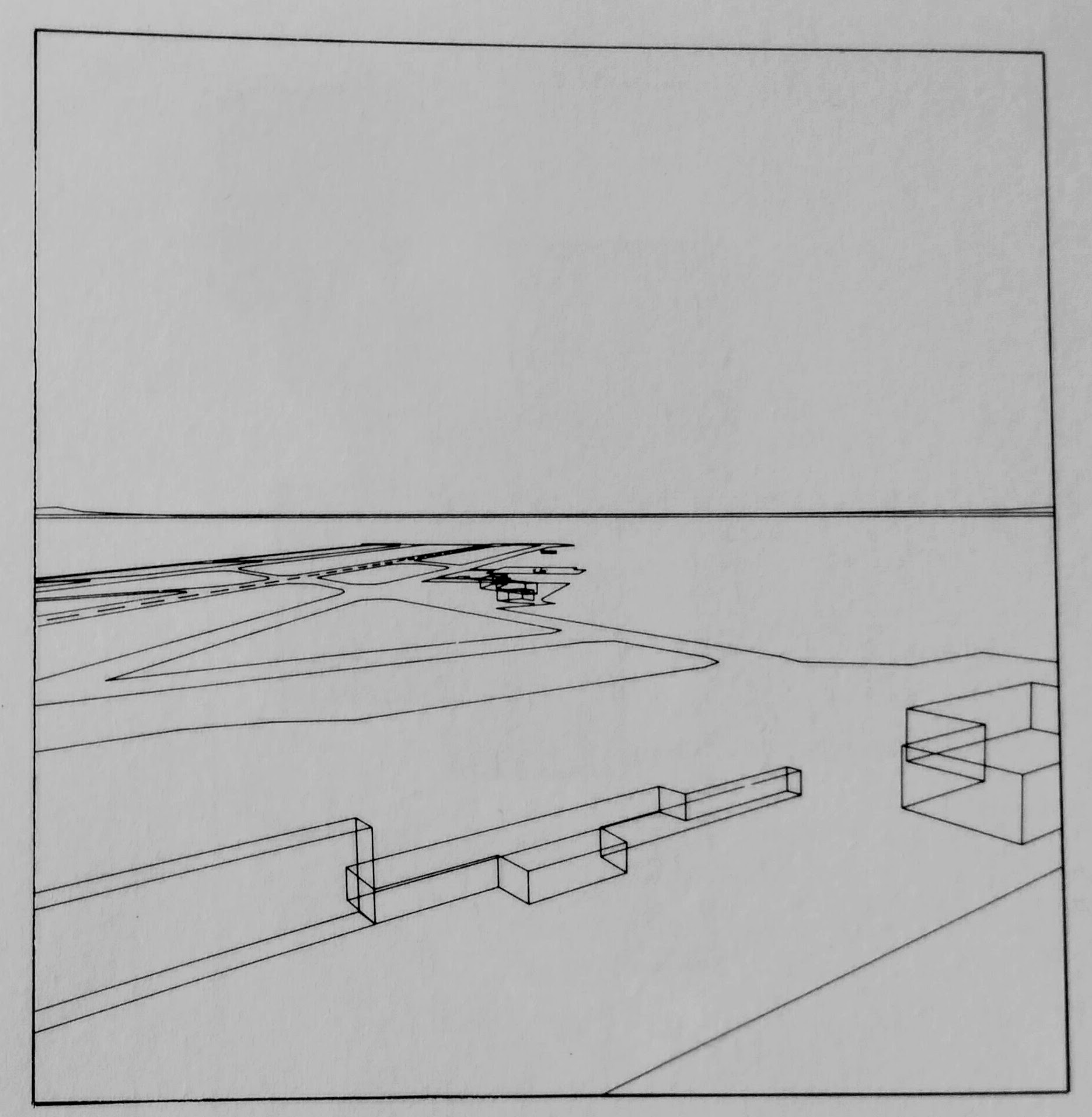

The term ‘computer graphics’ was first coined by the Boeing Company in the 1960s 9. The company used them to simulate landings on the runway and to determine the possible movements of a pilot sitting in the cockpit. They were also the first to animate simulated landings for pilot trainings. Computer graphics also turned out to be really useful in fields like architecture where simulations could be made.

left: Boeing airplane cockpit simulations. right: Seattle-Tacoma airport simulations for pilot traning 10

left: Boeing airplane cockpit simulations. right: Seattle-Tacoma airport simulations for pilot traning 10

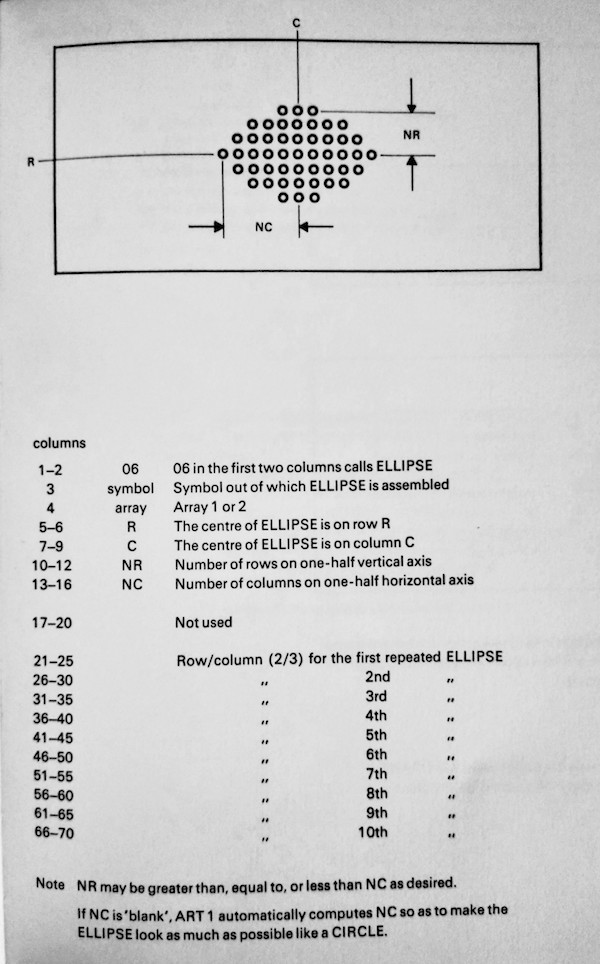

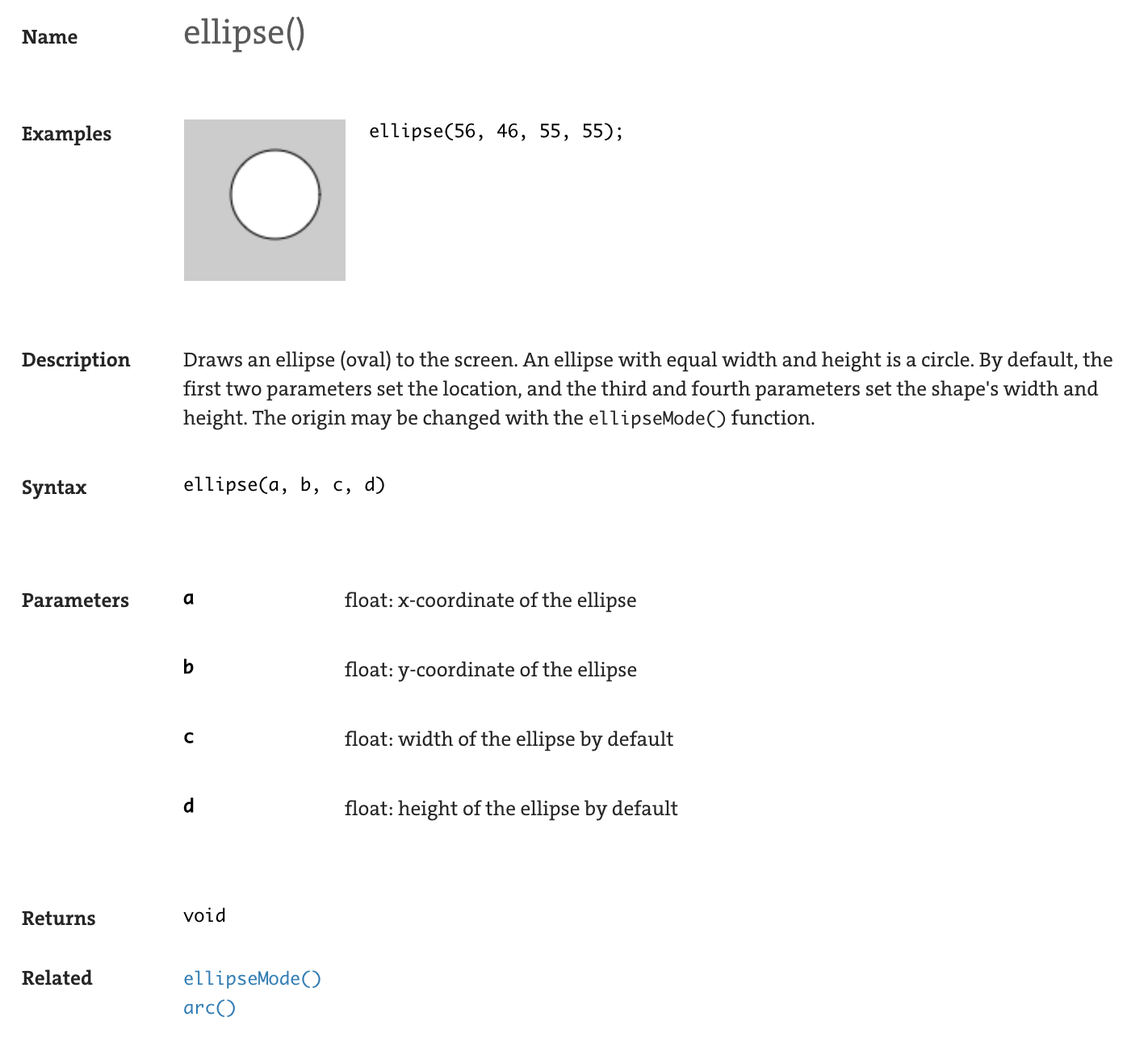

It wasn’t until later in the 1960s and 70s when more artists had access to the computer. Sometimes this happened in universities, where the computer lab would also be made available to students from other departments. A nice example of this collaboration was at the University of New Mexico, where Katherine Nash, Professor of Art and Richard Williams, Professor of Computer Engineering created the ART 1 programming language, which was designed to teach students to make simple computer graphics. It was designed to make programming accessible to those without a a technological background 11. For those of you who have heard of Processing or p5.js, maybe dabbling in generative art today, doesn’t that sound familiar? ART 1 was the original Processing! Processing is a popular Java-based language used widely today to create generative art. It’s rather nice to know that the idea of having an accessible programming language for non-technical folks to create art is very much relevant today. I’ll explore early programming languages for graphics later in this series.

left: A page from the ART 1 manual, detailing the parameters for drawing an ellipse 12, right: Everything you need to know to draw an ellipse in Processing13. The syntax for the latter is much more intuitive than the former.

What’s next

I hope that sets the scene a little bit for the articles to follow. Digital computing has only been around for 70 years and already so much has changed. Just one generation ago people were programming with punch cards. I grew up in an age where personal computers were already the norm. Heck, my earliest memory of a computer was playing Puzzle Bobble on our desktop computer at home.

Personally, antiquated technology is strange and fascinating at the same time, and I’m looking forward to exploring a little bit of it in hopes that understanding where we came from can help us understand where we are going.

Coming next will be Part 2: Plotters where I talk about the history of this delightful drawing robot machine. You can subscribe to my RSS feed to be updated when that goes out!

[edit] Part 2: Plotters is now up! Read here.

-

Casa, D. D. (2012). PDFs of “Computer Graphics And Art” [digital image]. Retrieved from https://toplap.org/pdfs-of-computer-graphics-and-art/ ↩

-

Michael, G. (n.d.). The IBM 7090 and 7094 Systems _Stories of the Development of Large Scale Scientific Computing at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Retrieved from http://www.computer-history.info/Page4.dir/pages/IBM.7090.dir/index.html ↩

-

7090 Data Processing System (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/exhibits/mainframe/mainframe_PP7090.html ↩

-

7090 Data Processing System (1958). Retrieved from https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/exhibits/mainframe/mainframe_PP7090B.html ↩

-

[CuriousMarc] (2014, Sep 7). 1964 IBM 029 Keypunch Card Punching Demonstration. Retrieved from Youtube ↩

-

Noll M. (2016). Leonardo, Volume 49, Number 3, (pp. 232-239) ↩

-

Preston S. (1965). Reputations Made And in Making. Retrieved from https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1965/04/18/101539366.pdf ↩

-

Noll M. A. (2016). Leonardo, Volume 49, Number 3, 2016, (pp. 232-239) ↩

-

Reichardt, J. (1971). The Computer in Art (pp. 15) ↩

-

Reichardt J. (1971). The Computer in Art (pp. 16) ↩

-

Reichardt J. (1971). The Computer in Art (pp. 40) ↩

-

Reichardt J. (1971). The Computer in Art (pp. 16) ↩

-

_Processing ellipse() documentation__ (2018). Retrieved from https://processing.org/reference/ellipse_.html ↩